Sirens

Biology

Anatomy

Sirens are viviparous, meaning they have live birth.

Some sirens have stripes, but they can’t see them due to the difference in perceived light lengths compared to other species. Most other humanoid species can see sirens’ stripes, and there is a recurring trend amongst young sirens to swim to other islands with humans on them to buy portraits of themselves to see their stripes.

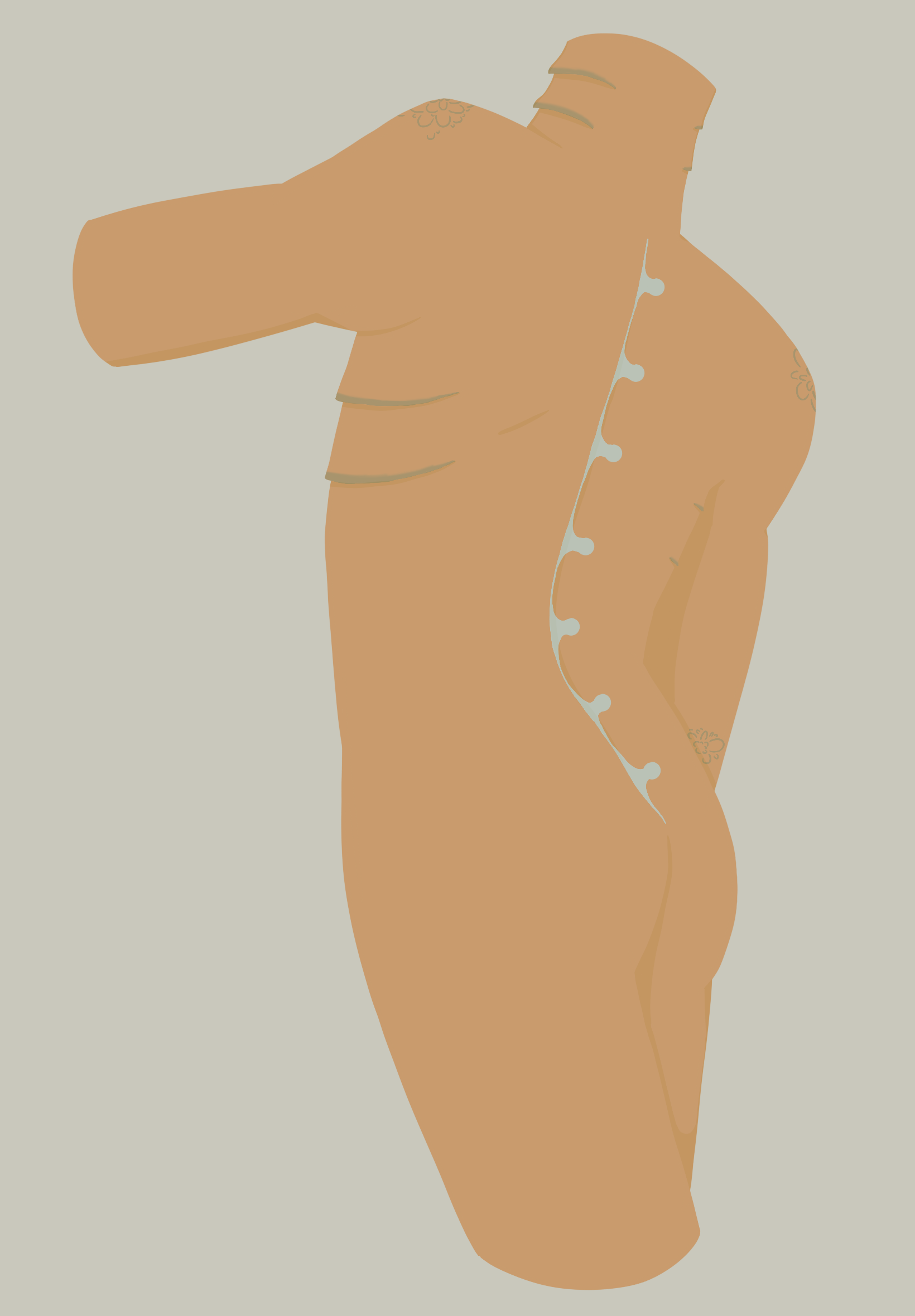

Sirens have naturally blue-ish green bones due to the amount of copper in the Fulican Archipelago.

Part of a siren’s ability to quickly adjust to drastic changes in light levels is due to their pupil’s ability to change shape. In lighter areas or out of the water, sirens will have round pupils, much like other humanoids, which dilate and contract based on how much light they’re being exposed to. However, in darker, deeper areas of the ocean, their pupils will contract more vertically, resulting in horizontal split pupils, which allow them to see a wider range of their surroundings, making it easier for them to spot incoming predators. Sirens also have light sensors along their spines, which allow them to sense things moving above and/or behind them while swimming.

Image 1. The back of a siren, showing light sensors, and gill placement and coloration

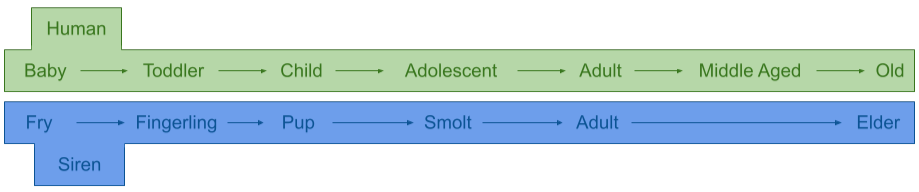

Figure 1. The life stages of sirens and human equivalents

Lifecycle

Fry (Birth-1) Though sirens do develop quite similarly to humans and other similar species, one main difference is the speed of development at the fry stage. Fries can often swim within hours of birth. They cannot breathe air, and are sensitive to light, spending this entire stage underwater. During this stage, they will develop their vision (which is often not very strong), limb strength, and swimming ability, but they usually can’t dive more than 10 feet underwater. Most fries can communicate through sfyrízon, a special system of clicks and whistles used for underwater communication, by the time they’re one year old.

Fingerling (2-4) Already accustomed to life underwater, the main task of any fingerling parent is to now acquaint their child with living on land. The fingerling stage usually involves development in crawling and walking, as well as beginning to learn to speak. Fingerlings are less sensitive to light than fries, but are still more susceptible to sunburn or skin damage above water than older sirens. They require more time in water as well, as their sensitive skin dries out quite quickly. Also during this development stage, fingerlings’ eyes become stronger, allowing them to not only see in the dark, but also to transition more quickly from light areas to dark ones. By the end of this development stage, most fingerlings can both swim and walk, can communicate in the local language, and can dive up to 50 feet underwater, and have a fully developed swim bladder, which allows them to control their buoyancy. Their light sensors begin to develop around age 3, and are especially sensitive during the fingerling stage.

Pup (5-11) The pup stage is where sirens and humans once again begin to look more similar in physical and mental development. During this stage, they begin to learn to read and write, develop a sense of individuality, and usually learn emotional regulation. Also during this development stage, siren pups learn to hunt for themselves, and can spend more time out of the water. They are less sensitive to sunlight, and have strong arms, legs, and lungs. Pups between ages 5 and 8 can dive up to 80 feet underwater, while older pups usually reach about 100. They also grow claws during this stage, which are beneficial for both hunting and self defense. At the end of this stage, around age 10 or 11, a pup will begin to go through sexual maturation, called efiveía, which lasts until around the middle of the smolt stage.

Smolt (12-20) The smolt stage is one of the longer stages of siren development, lasting from what humans would call “tweendom” to the middle of human “young adulthood.” During this stage, emotional and physical development continue, and efiveía ends, though there is a concern for the physical safety of smolts who have the ability to carry a child, even once they are sexually mature. Smolts finish developing their claws around age 15, and are fully able to hunt for themselves. They also have better hearing, and their eyes can transition much more quickly from dark to light than fingerlings or pups. By the end of the smolt stage, they can dive over 400 feet underwater.

Adult (21-49) The longest defined stage in siren development, adult sirens don’t actually grow or change physically in a way that is notable, compared to previous stages, though they’re usually able to dive further than smolts, with the deepest recorded siren reaching over 1000 feet underwater. Also during this stage, sirens often begin to mate and form nests, usually hatching a brood of up to 10 fries, usually between two or three mates. At the end of this stage and into the elder stage, adult sirens with the ability to bear children experience avgoútélos, similar to human menopause, and are no longer able to bear children. Non-childbearing adults are still able to sire offspring, but the ability diminishes as they age.

Elder (50+) The final stage in the siren lifecycle, elder sirens often begin to experience a decrease in physical qualities, including dull or brittle claws and increased skin sensitivity, as well as drying out faster while on land. Elder sirens often also experience hearing loss, a loss of sensitivity in their light detecting organs, and diminished swimming strength. However, the deterioration in elder sirens is quite less than that of their human counterparts. The average lifespan of a healthy siren, irregardless of sex or gender, is 92-years-old, with the oldest recorded siren living to 134-years-old.

Society & Culture

Nests

IMPORTANT TERMS

Clutch A group of adult sirens and their children, organized based on parentage, mate order, and birth order

Brood All of the children of one childbearing siren

Nest The place that a clutch lives

Mates/Partners/Spouses While mate is the technical term for a pair of sirens who have had children together, the more common terms are partner, spouse, husband, and wife, and are used interchangeably. There is no formal marriage ceremony in any siren culture. Two sirens become partners when they have a child (or plan to have a child) together, and this relationship can be severed at any time.

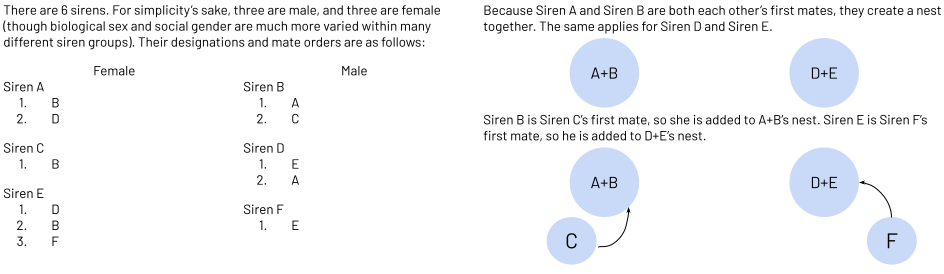

Figure 2. An explanation of relationship dynamics within a clutch

Nests are organized based on the original pair in a clutch. In cases of cross-nest mating, the non-childbearer is the one who splits time, often focusing more time on whichever nest has their youngest child. In the above example, when D and A mate, D now has to split time between both nests.

Non-childbearing sirens looking for second, third, etc. mates often do not look outside their own island, as, should they mate with a child-bearing siren who already has their own nest, they don’t want to have to travel too far to see their children.

Children always live in the nest of the child-bearing parent, but after their coming of age ceremony (16) they are free to live in either parents’ nest. Most children start their own nest after age 20.

WHERE ARE NESTS BUILT?

Most nests are dug into the rocky crevices underwater in and around the childbearer’s home island.

Nests very often do not have doors, or will have curtains instead of doors. Very few buildings on land in villages have locks. Exceptions are most often stores with expensive stock, and private rooms at inns.

Because space can run out quickly, many newer nests also have additions above water, either in buildings in the small towns (which are primarily stores and inns for non-sirens) or on small boats. This is especially common in the highly-populated Vráchos.

Nests can be reused, though there are rules to this. A pair of sirens can only use abandoned nests from the bloodline of the parent that bore them, which means that the ending of some bloodlines has rendered old nests unusable.

Ruling Structure

Sirens in the Fulican Archipelago do not have a central governing body of any type. Society is organized around parents and the clutch. Social hierarchies are based upon several factors, primarily age, but also parentage and the relationships of ones’ childbearing parent to other parents within a clutch.

Religion

Siren religion is most similar to human animism, which believe that all things, animate or inanimate, possess a soul or spirit which give them agency and autonomy. Because of this, all objects and creatures are treated as equal to the siren, and it is viewed as sinful to kill a plant or animal, or to damage structures or natural formations without asking permission and sufficiently apologizing, and utilizing the yielded materials to their full extent of use.

Coming of Age

At the end of the smolt stage of the lifecycle (between 20 and 22 years of age), sirens are often given shells and rocks collected by their birth parents and brood-mates. These shells and rocks are intended to be used as nest presents for their first partner. After finding a mate, young sirens are then expected to search for an open nest, or are given access to an empty nest which they have inherited through the lineage of the parent who bore them. If no nest is available in the immediate area, they may leave to find a less populated location, or they may dig out their own nest.